Real-world 3D data can be messy. Point clouds, for instance, can be noisy, non-uniform, and can have varying densities. A given point cloud may not even follow a manifold. Similarly, 3D meshes can be complex and irregularly sampled; the triangulation may not be "regular" (skinny triangles or non-equilateral triangles), and may contain non-manifold edges and vertices. These may arise from the usual 3D data collection techniques such as LiDAR or 3D scanning. The scanning procedure itself may introduce non-manifold edges or vertices in the mesh.

When dealing with any 3D surface, a go-to operator is the Laplace-Beltrami operator, represented by . It is so fundamental that Laplace-Beltrami is to surface Geometry what the Fourier basis are for periodic functions. The functions on the (Riemannian) manifold can be decomposed into eigenfunctions of on that manifold, similar to how periodic functions can be decomposed into Fourier series.

Discretizing the Laplace-Beltrami Operator

When discretizing the Laplace-Beltrami operator over discrete structures like point clouds or meshes, we encounter problems - specifically we lose some important properties of the continuous Laplace-Beltrami operator.

When working on discrete structures, the following are some crucial properties we would like our Laplacian to have -

- Symmetry - The Laplacian should be symmetric i.e. , where is the weight of the edge in the mesh in the Laplacian matrix .

- Locality - The weight for vertices and that do not share edges in the given mesh . In other words, any change in the function at a distant point should not affect the action of the Laplacian in the local region. This results in a sparse Laplacian matrix.

- Positive - The weights for . This ensures that the flow is from regions of higher potential to regions of lower potential and not vice-versa.

- Linear Precision - The Laplacian action must be zero whenever the mesh is line embedded into the Euclidean plane and is any linear function on the plane. This means that both the tangential and normal components of the Laplacian at a planar surface must be exactly zero. This is important for preserving the planar regions under parameterization.

The above properties are so chosen as to reflect those properties of the continuous Laplace-Beltrami operator that make it so useful in geometric processing. For example, the Linear precision property is highly useful in denoising and smoothing operations. The Symmetry and the Positive properties are the sufficient conditions for a positive semi-definite (PSD) Laplacian and one that satisfies the Maximum Principle[1]. The Locality and Positive properties ensure that the discrete Laplacian follows the diffusion process just like the continuous Laplace-Beltrami operator .

Satisfying all the above syncretic properties is hard. In fact, Wardetzky et. al proved a No-Free-Lunch theorem[2] showing that it is impossible to satisfy all the above properties simultaneously for any discretized Laplacian. Imagine a world where DFTs do not satisfy the orthogonality property! The Horror!

The Cotan Laplacian is a widely used approximation of discrete Laplacian. It is so chosen as it satisfies the Symmetric, Locality, and Linear Precision properties[3]. In fact, the Cotan Laplacian also satisfies another important property - its solution to the discrete Dirichlet problem converges to the solution of the smooth Dirichlet problem[4] involving . This makes Cotan Laplacian an indispensable choice for solving PDEs on meshes. Besides, it also works well on irregular vertex distributions in practice.

The general way to construct the Cotan Laplacian is to define a local cotan Matrix for each triangle in the mesh

Where . The entries of these local cotan matrices are then summed up into corresponding entries of a global laplacian . The associated mass matrix is a diagonal matrix defined as

Where is the area of tringle incident of the vertex .

The Cotan Laplacian, although widely applicable, does not satisfy the Positive property, even if it is PSD. This implies that the Maximum Principle is not satisfied by the Cotan Laplacian. A variation of the Cotan Laplacian is the Intrinsic Laplacian, which applies the Intrinsic Delaunay Triangulation over the given mesh and then constructs the Laplacian over this triangulated mesh.

A particular triangulation is intrinsic Delaunay if every interior edge shared by triangles and satisfies the following condition

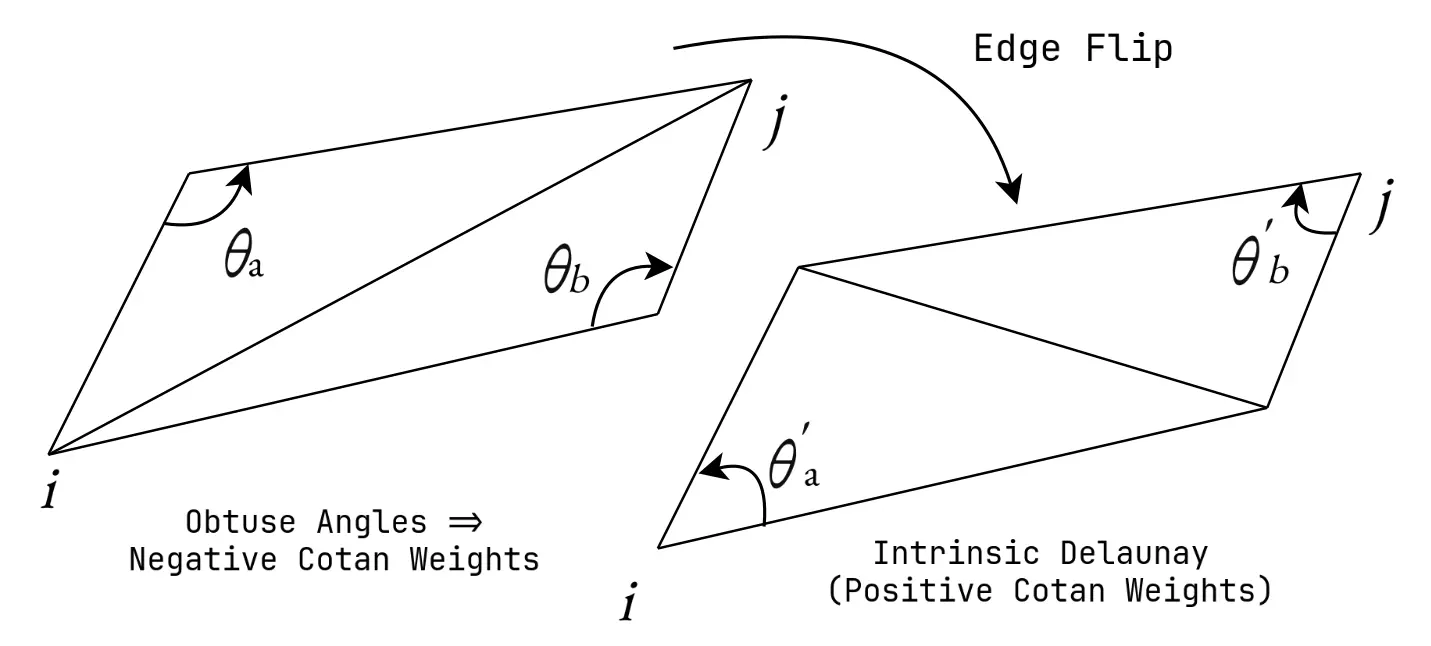

Where is the interior angle at vertex of the triangle . As evident from above, under this intrinsic triangulation, the Cotan Laplacian becomes Positive. Furthermore, any given triangulation can be converted to intrinsic delaunay via finite number of edge flips.

Obtuse triangles lead to negative Cotan weights. A simple edge flip can resolve this issue and lead to intrinsic Delaunay triangulation with positive weights.

As fated by the previously mentioned No-Free-Lunch theorem, the Intrinsic Laplacian loses the Locality property. The intrinsic Laplacian generally satisfies geometric locality - every vertex of a Delaunay triangulation is guaranteed to be connected to its closes neighbours. Although the it does not satisfy the combinatorial locality, the geometric locality is often sufficient for many applications. Nonetheless, the intrinsic Laplacian is not as sparse and may fail in cases where the local neighbourhood may be different from the input mesh.

Extending the Laplacian to Non-Manifold Structures

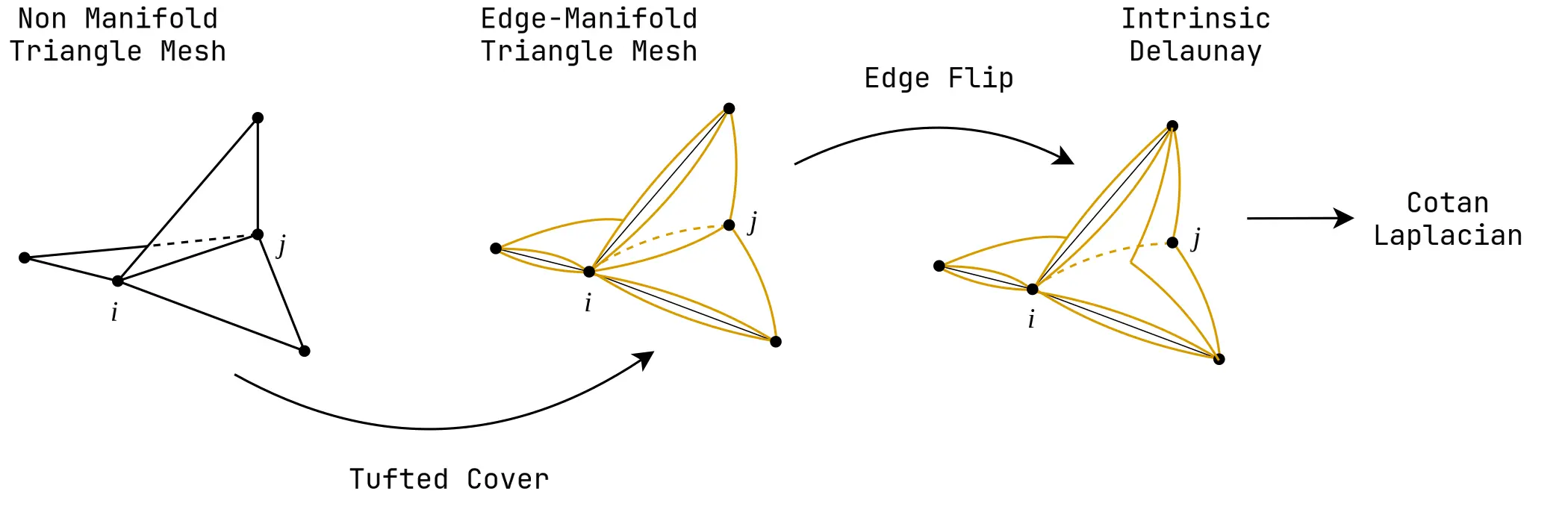

Both the Cotan and its intrinsic variation are defined only for manifold structures. The intrinsic Laplacian requires at least an edge-manifold. So, the goal is to convert the given non-manifold to at least an edge-manifold. We can then use edge flips to get an intrinsic Delaunay triangulation, and finally the Cotan Laplacian.

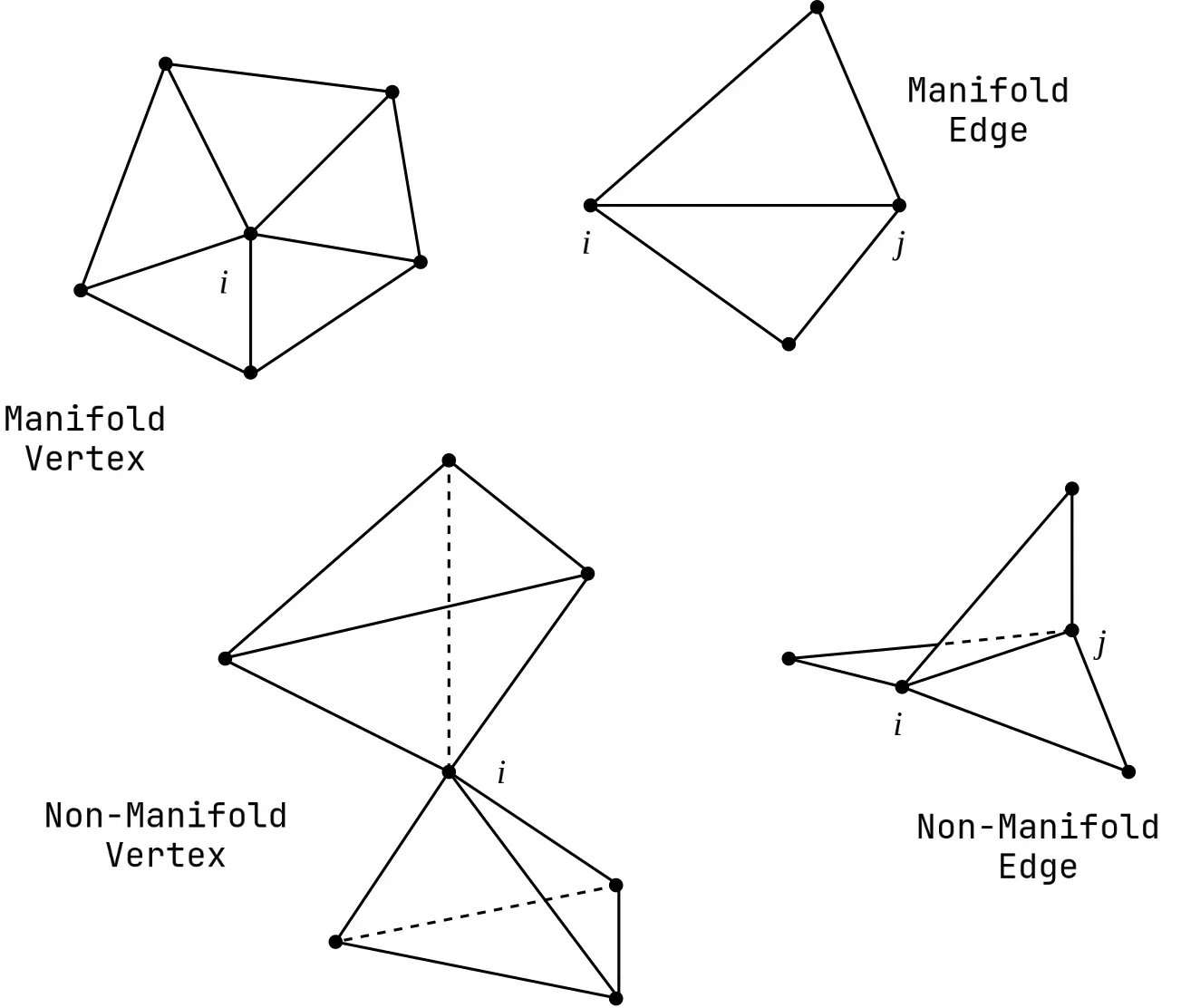

A quick refresher on the manifold property: An interior vertex is manifold if the boundary of all edges incident on form a loop or a path of edges. In simpler terms, the polygons containing each vertex must form a single "fan". An interior edge is manifold if it is contained in exactly one or exactly two triangles. Or in other words, every edge must be contained in only two polygons or one polygon (no "fins"). The following figure illustrates the manifold conditions.

A recent paper by Sharp et. al.[5] introduces an elegant technique to convert the non-manifold mesh into edge-manifold mesh. They observe that the edge flips still work for cases where the mesh is edge-manifold but has non-manifold vertices. From this, the idea is then to add duplicate faces at edges where the mesh is non-manifold. This makes it an edge-manifold, but makes the interior vertices non-manifold. Yet, we can still perform edge flips on these duplicate faces (called tufted covers) to get a proper intrinsic Delaunay triangulation. Thus, by adding a tufted cover, any non-manifold edge can be converted to an edge-manifold as the previously shared face is now two separate faces.

The important aspect of the above tufted cover [6] procedure is that the vertex set is preserved - we are only adding superficial faces (tufted cover) to the vertices to get an intrinsic Delaunay triangulation from which we can obtain the Cotan Laplacian. Recall that the Laplacian is a matrix, where is the number of vertices.

Therefore for given any triangulated mesh, manifold or not, it is possible to compute an approximate discrete Laplacian. A library for computing the tufted-cover Laplacian is available from the authors here.

The above procedure is more attractive for point clouds as traditional point cloud Laplacians try to approximate a local manifold using a -NN graph. The neighbourhood size is usually chosen based on the local density of the point cloud, in-turn increasing the computational complexity. Furthermore, such sampling may result in loss of small or thin features in the point cloud, which are often found in real-world data. To reduce the computational complexity, a mesh Laplacian if often preferred - the point cloud is converted to a mesh and then the Laplacian is computed. The tufted-cover procedure improves upon this with just local triangulations[7] (may have irregular connectivity and non-manifold structures) over the input point cloud.

As with any procedure, the result is only as good as its input data. The authors suggest that the input mesh/point cloud be free of topological noise, defective meshes, and isolated vertices before applying the tufted-cover procedure.

| [1] | The Maximum Principle is satisfied on a given manifold if the function on that manifold achieves maxima/minima at the boundary of the manifold. Physically, one may think of the heat diffusion over a metal rod where the temperature along the rod can never be the highest/lowest compared to the temperature at the ends of the rod. |

| [2] | Wardetzky, Max, et al. "Discrete Laplace operators: no free lunch." Symposium on Geometry processing. Vol. 33. 2007. pdf |

| [3] | The Cotan Laplacian has been derived by many authors in different contexts, the earliest of which goes back to 1949 by MacNeal. Refer to Laplace-Beltrami: The Swiss Army Knife of Geometry Processing by Justin Solomon, Keenan Crane, and Etienne Vouga. Link |

| [4] | The Dirichlet problem (closely related to the above Maximum Principle) is the solution of a specified PDE, given the values on the boundary of the domain. The solution to the Dirichlet problem involves the Laplace-Beltrami operator as . The usual physical interpretation is that, when a plate if heated/cooled at its boundary, the temperature of any interior point will reach some steady state, governed by the heat diffusion equation. |

| [5] | Sharp, Nicholas, and Keenan Crane. "A laplacian for nonmanifold triangle meshes." Computer Graphics Forum. Vol. 39. No. 5. 2020. Link |

| [6] | Highly recommend Nicholas Sharp's presentation where he shows a beautiful video of the tufted cover + intrinsic Delaunay triangulation (edge flip) process. |

| [7] | For local triangulation, we still need to compute the -NN graph. However, this is a fixed overhead to get a local triangulation as the actual Laplacian computation relies only the neighbourhood edges and vertices. |