Complex numbers often popup in strange and unexpected places. This cliché has become second only to . However, these clichès are indeed warranted. Besides from them popping up unexpectedly, one can also try to employ them in unexpected ways. Below are two such examples where leveraging complex numbers yields interesting and compact results.

1 : Complex Step Numerical Differentiation

The common naïve method for differentiating a function is given by the forward difference formula

where is the real finite difference interval and is the truncation error (from the full Taylor series of ). The above method is not accurate or computationally efficient, but it is quite easy to implement.

The common issue with implementing the above formula is the step-size dilemma, the tradeoff between choosing a small step size and a small resultant error. To reduce the truncation error, should be small as possible; however, too small a step size would result in numerical errors like subtractive cancellation, deeming the result inaccurate.

A slight numerical improvement to the equation (1) is the central difference formula.

Notice the truncation error is now dependent upon rather than . For , this is a considerable improvement[1].However, the plague of subtractive cancellation still persists.

Can we do any better? Enter complex numbers.

Consider an analytic function over complex variable as . Then, the Cauchy-Riemann equations are given by - Expanding the first equation by equation (1), we get where is real. Now, the class of functions that we are interested in are real, so and . Substituting these in the above equation, we get

Where is the imaginary part. Voilà! We have now eliminated subtraction from the differentiation formula! To evaluate how good the above formula is, we need to find the truncation error.

We have now obtained a numerical differentiation formula for a real function that does not suffer from subtractive cancellation, and has a significantly low truncation error. Owing to this, the above formula admits extremely low values of , even to the machine precision .

Implementing complex-step differentiation is extremely simple too.

import numpy as np

def complex_step_diff(func, x, h):

z = complex(x, h)

return np.imag(func(z) / h)

Comparison with Automatic Differentiation

The equation (5) and forward-mode automatic differentiations bears a close relationship. Consider the function . The differential can be computed by forward-mode autodiff and complex-step differentiation as follows.

Both methods yield the same result. The perturbations are stored in a separate variables in autodiff, while they are stored in the imaginary parts in complex-step differentiation. Compared to the forward (and reverse) mode autodiff that computes gradients based on perturbations at the level of machine precision[2], complex-step too can produce equally accurate gradients at the level of machine precision (refer to above figure).

However, complex-step differentiation is not applicable in cases where there is a complicated control flow in the computational graph of the function . These control flows often result in discontinuities. Complex-step differentiation requires specific tricks to handle each of these cases[3] while autodiff handles them in a more rigorous manner. Moreover, complex-step always performs additional computations compared to autodiff as shown in equation (7). For these reasons, autodiff should still be preferred.

2 : Complex Momentum Stochastic Gradient Descent

Consider the classical Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) algorithm with momentum as shown below.

Where is the function whose parameter is being optimized at step , is the velocity accelerated by the momentum , and is the learning rate. Usually, the momentum value is set to be positive (). However, one can argue that the momentum value should actually depend upon the loss landscape, just like the learning rate . A lot of effort has been put into automatically adapting the learning rate based on the local loss landscape. SGD modifications like RMSProp, and Adam[4], apart from a range of learning rate schedulers have been developed to make the optimization work on a variety of different objectives and loss landscapes.

One may extend the idea to momentum as well. Indeed, it has been shown that first-order method like SGD with positive momentum do not converge for adversarial problems like GANs. GANs, given their dueling networks design, represent a zero-sum game. One player - the Generator maximizes their chance of fooling the Discriminator , while the Discriminator minimizes their chance of getting fooled. This is mathematically represented as

Where is the objective function that captures the dueling dynamic. In its general form, it is written as [5], where is some function.

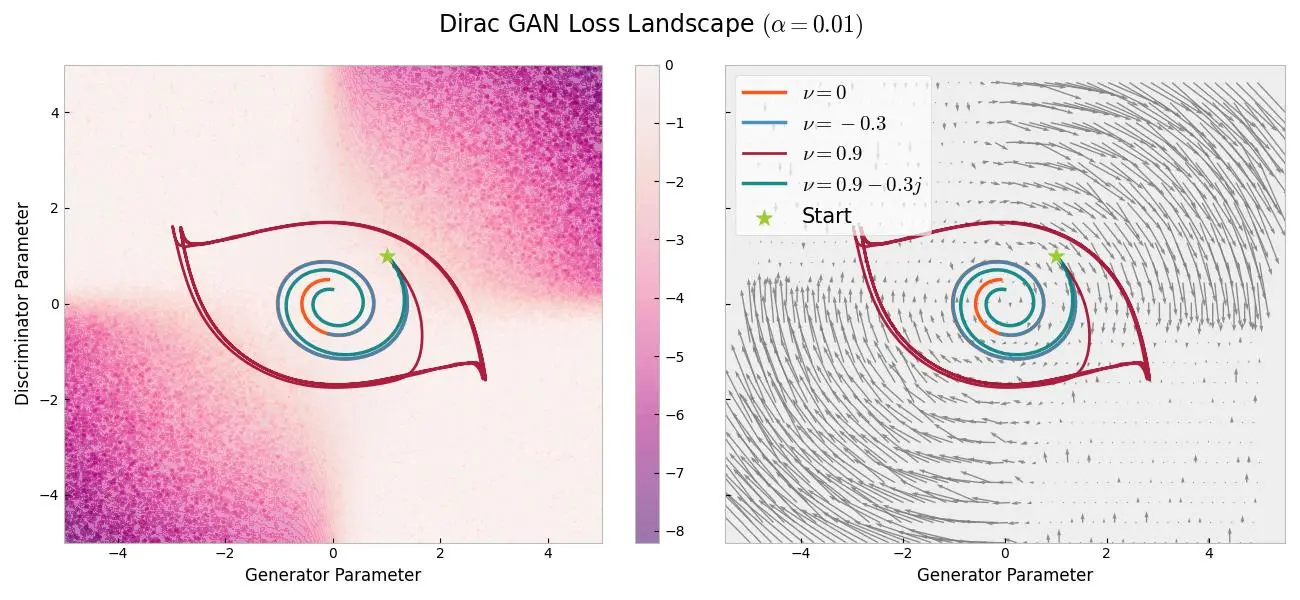

Behold, the eye!

The above figure shows the training trajectories of Dirac GAN[6] with learning rate across various momentum values - no momentum(), positive, negative, and even complex momentum. Intuitively, if positive momentum is akin to a heavy ball that accelerates the gradient descent, negative momentum is like friction that slows it down[7]. From the above figure, the training converges for all momentum values except for a positive-valued momentum ().

If positive momentum values work well for non-adversarial problems, and negative momentum works for adversarial problems, what if we use a complex valued momentum ? That way, we may obtain a more generic first-order optimizer. That exactly what Lorraine et. al. did[8]. We can directly modify the equation (8) for a complex0valued momentum as

Where and are the real and imaginary parts respectively.

2D GAN on Toy data with complex-momentum

In practice, complex-momentum SGD requires 2 momentum buffers (for the real and imaginary parts) and is quite easy to implement.

import torch

class ComplexSGD(torch.optim.Optimizer):

"""

SGD with Complex-valued Momentum

"""

def __init__(self,

params,

lr:float,

momentum:torch.cfloat,

device='cpu'):

"""

Args:

params (Iterable): Iterable list of parameters

lr (float): learning rate

momentum (torch.cfloat): complex momentum value

device (str, optional): device to run on. Defaults to 'cpu'.

Returns:

None

"""

super().__init__(params, defaults = dict(lr=lr))

self.momentum = torch.tensor(momentum)

self.momentum.to(device)

self.state = dict()

for gr in self.param_groups:

for p in gr['params']:

self.state[p] = dict(velocity = torch.zeros_like(p,

dtype=torch.cfloat,

device=device))

def step(self):

for gr in self.param_groups:

for p in gr['params']:

self.state[p]['velocity'] = self.state[p]['velocity'] * self.momentum - p.grad

p.data += (gr['lr'] * self.state[p]['velocity']).real

The advantage is that complex-momentum SGD offers a much more generic algorithm that is applicable to adversarial and non-adversarial (sometimes called cooperative) problems, and everything in between. Consider the following minmax objective.

Where are coefficient matrices, and controls the "adversarial-ness" of the objective. When , the first tem vanishes and and can be optimized independently. Thus, it becomes a purely cooperative objective. This is the regime where positive momentum works best. When , the above equation reduces to the first term and the problem becomes purely adversarial. For such problems, the complex-momentum SGD provides a one-stop solution.

Conclusion

The point of this discussion to shed some light on the usefulness of complex numbers in constructing a compact yet powerful representation of a more sophisticated procedure. In the above two examples, the complex representation did not solve any problem uniquely, but was shown to be equivalent to or a generalization of other standard procedures.

| [1] | Refer to this stackexchange answer for a derivation. |

| [2] | Refer to chapter 3 of Griewank, A. and Walther, A., 2008. Evaluating derivatives: principles and techniques of algorithmic differentiation. SIAM. |

| [3] | Examples of handling special control flows can be found in Martins et. al.'s paper. |

| [4] | The squared-gradient terms that you see in RMSProp, Adam etc, is basically an approximation of the local curvature (Hessian) of the loss landscape. These techniques adapt the learning rate using this local curvature, although from the way they are written in literature, one may think of them as modifying just the velocity factor. |

| [5] | Nagarajan, Vaishnavh, and J. Zico Kolter. Gradient descent GAN optimization is locally stable. Advances in neural information processing systems 30 (2017). |

| [6] | Mescheder, L., Geiger, A., & Nowozin, S. (2018, July). Which training methods for gans do actually converge?. In International conference on machine learning (pp. 3481-3490). PMLR. ArXiv Link |

| [7] | Gidel, G., Hemmat, R. A., Pezeshki, M., Le Priol, R., Huang, G., Lacoste-Julien, S., & Mitliagkas, I. (2019, April). Negative momentum for improved game dynamics. In The 22nd International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics (pp. 1802-1811). PMLR. ArXiv Link |

| [8] | Lorraine, J.P., et al. Complex momentum for optimization in games. International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics. PMLR, 2022. ArXiv Link |